EPR’s Impacts on Small and Medium Canadian Fashion Businesses

-

Deborah King

- EPR, Fashion, Sustainability

Executive Summary

Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) is increasingly being considered as a legislative tool to address textile waste in Canada. Framed as a way to promote sustainability and reduce landfill-bound textiles, EPR shifts the responsibility for end-of-life garment management onto producers. However, this policy risks placing a disproportionate burden on small and medium-sized fashion businesses—those that make up the majority of the Canadian industry and are often the most committed to ethical and local production.

Standardized compliance requirements and the absence of scalable textile recycling infrastructure raise serious questions about whether the policy can deliver meaningful or equitable outcomes. By failing to address overproduction—the primary driver of fashion waste—or distinguishing between different business models, EPR risks entrenching existing disparities within the industry. Large multinational brands are better positioned to absorb additional costs and manage complex reporting obligations, while small, independent labels may face increased financial strain, diminished competitiveness, and less freedom to innovate.

In addition to these quantifiable impacts, EPR may introduce more subtle, systemic shifts that further narrow the landscape for independent fashion in Canada. Barriers to entry for emerging designers, a move toward product standardization, and a growing sense of risk aversion among small brands all point to a future where creativity and diversity may be constrained rather than encouraged.

As it stands, EPR risks reinforcing the very issues it claims to solve—placing undue strain on small, sustainable businesses while leaving the root causes of textile waste untouched. Proceeding without addressing these structural gaps could unintentionally destabilize the very industry it seeks to reform.

"small and independent Canadian brands—many of which are already operating with limited resources and a strong commitment to ethical production—may struggle to keep pace. The result could be a system that inadvertently rewards scale over sustainability, creating market distortions that threaten innovation, diversity, and long-term competitiveness within Canada’s fashion ecosystem."

1.0 Introduction

The fashion industry is frequently cited as one of the world’s most polluting, largely due to overproduction and waste generated by fast fashion. In response, policymakers in Canada and abroad are turning to Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) as a regulatory tool to oversee textile waste. While the policy is framed as a way to hold producers accountable, EPR introduces additional costs and compliance obligations—regardless of a brand’s sustainability practices. In doing so, it risks placing disproportionate strain on small and independent labels already committed to ethical production, while doing little to stem the tide of cheap, unsustainable fast fashion imports. Without confronting this imbalance, can EPR truly deliver the change it promises—or will it hinder the very progress it aims to support?

This article takes a deep dive into the potential impacts of EPR on Canada’s fashion SMEs, exploring:

2.0 The Current State of the Canadian Fashion Industry: A Landscape Built on Small Businesses

Small businesses are the backbone of the Canadian fashion industry. In fact, 98% of Canadian fashion businesses (NAICS 315) have fewer than 99 employees, relying on local production facilities that prioritize sustainability and ethical practices. However, maintaining responsible production in Canada comes with challenges.

Unlike large corporations that leverage high order volumes to negotiate better supplier terms, small brands pay more for materials and often face longer lead times. Economic instability—whether from pandemics, inflation, or political uncertainty—can disrupt consumer spending, making it difficult for these businesses to maintain steady sales.

The biggest challenge, however, comes from fast fashion giants. Companies like Zara, H&M, Shein, and Uniqlo dominate the Canadian market with rapid production cycles and ultra-low prices. Their ability to churn out trendy, inexpensive clothing puts enormous pressure on smaller brands, forcing them to either compete on price—at the cost of quality and sustainability—or struggle to maintain their market share.

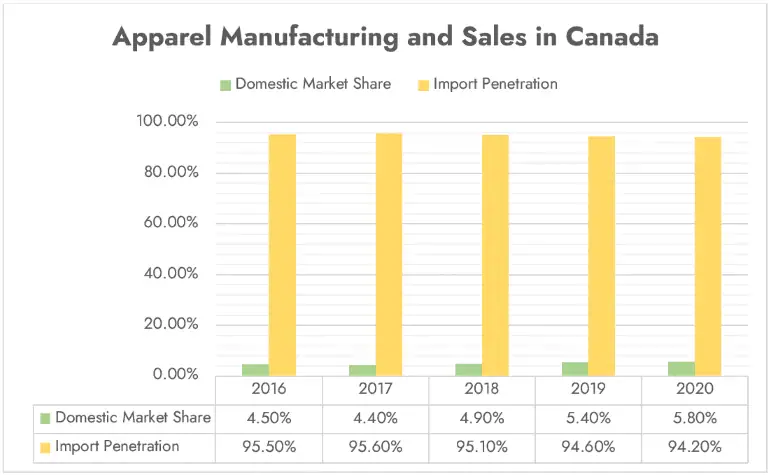

Fast fashion’s dominance isn’t just about price—it’s also about sheer volume. According to the latest available trade data, as of 2020, at least 94% of clothing sold in Canada was imported (Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada, 2021). This represents a significant share of the apparent domestic market, which averages $13.7 billion CAD annually. Such heavy reliance on overseas manufacturing further tilts the playing field in favor of large multinational brands, which benefit from lower labor costs, massive production facilities, and streamlined global supply chains.

3.0 Assessing Canada’s Readiness for EPR Implementation in Fashion

3.1 Current State

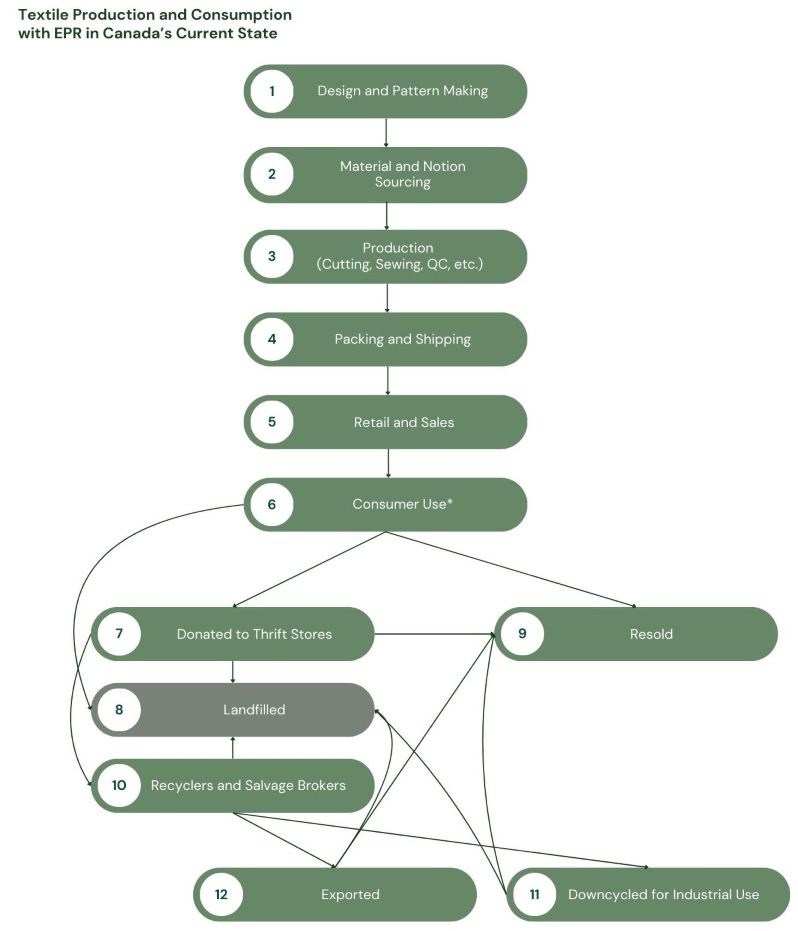

At a high level, the production and consumption cycle of clothing in Canada follows a pattern similar to the diagram below. After consumer use, clothing typically follows one of two paths: it is either donated to thrift and second-hand stores or discarded in landfills.

a) Misrepresented Textile Waste Statistics

It’s challenging to quantify how much textile waste ends up in Canadian landfills, as there is no national system to track discarded textiles, and waste is not sorted at the time of disposal. Despite this data gap, a widely circulated—and incorrect claim—continues to appear in credible publications: that the average person throws away 85% of their clothing rather than donating or recycling it.

This figure stems from a misinterpretation of data reported by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). The EPA distinguishes between textiles sent to US landfills and those labeled as “recycled,” with the latter based on estimates from industry and state agencies that recover materials through independent collection systems. However, this recycled category does not include clothing donations or second-hand reuse (United States Environmental Protection Agency, 2024). As a result, claims like the 85% figure exclude the impact of second-hand markets and reuse efforts—leaving out an important part of the textile waste story.

Even without accurate donation data, it’s clear that textile waste is on the rise. The EPA links this increase to a 182% surge in textile and apparel imports into the U.S. between 2000 and 2023 (U.S. Government Accountability Office, 2024). Canada is following the same pattern, with fast fashion imports flooding the market and driving even more waste.

b) Estimating Textile Waste in the Canadian Landfill

According to Environment and Climate Change Canada, 36.5 million tonnes of solid waste was landfilled in 2022 (Environment and Climate Change Canada, 2024). In the same year, Statistics Canada reported that 65,818 tonnes of textile waste was diverted from landfills (Statistics Canada, 2024).

Because waste isn’t sorted upon disposal, national textile waste estimates are typically based on extrapolations from localized municipal studies—where data from a single region is applied to the entire country. As a result, estimates can vary widely, as seen in the following figures:

• 481,000 tonnes (Fashion Takes Action, 2021)

• 955,265 tonnes (National Association for Charitable Textile Recycling, 2019)

• 500,000 tonnes (University of Waterloo, 2023)

Based on these estimates, textiles account for approximately 1.3% to 2.6% of total landfill waste in Canada.

c) Recyclers and Salvage Brokers

Not all donated textiles make it to resale. Items that are soiled, wet, mildewed, or otherwise contaminated are often landfilled upon receipt. Additionally, many textiles that do not sell in thrift stores are redirected to recyclers and salvage brokers.

These companies operate independently and are not required to track or publicly report their data (U.S. Government Accountability Office, 2024). However, they manually sort textiles into three main categories:

| Category | Criteria | Typical Fate |

|---|---|---|

| Reusable Clothing | Good condition, wearable (but unsold locally) | Exported for resale (overseas) |

| Downcyclable Textiles | Non-wearable but clean, durable fabrics | Downcycled into industrial products |

| Non-recyclable Waste | Heavily contaminated or difficult to process | Landfill or waste-to-energy |

Downcycling and Industrial Applications

Textiles classified as downcyclable undergo mechanical recycling and are repurposed into industrial products, such as:

• Industrial wiping rags (used in manufacturing and cleaning)

• Automotive & furniture padding (car seats, upholstery)

• Building insulation

• Carpet underlay

• Stuffing for pillows, mattresses, and pet beds

3.2 What changes with EPR?

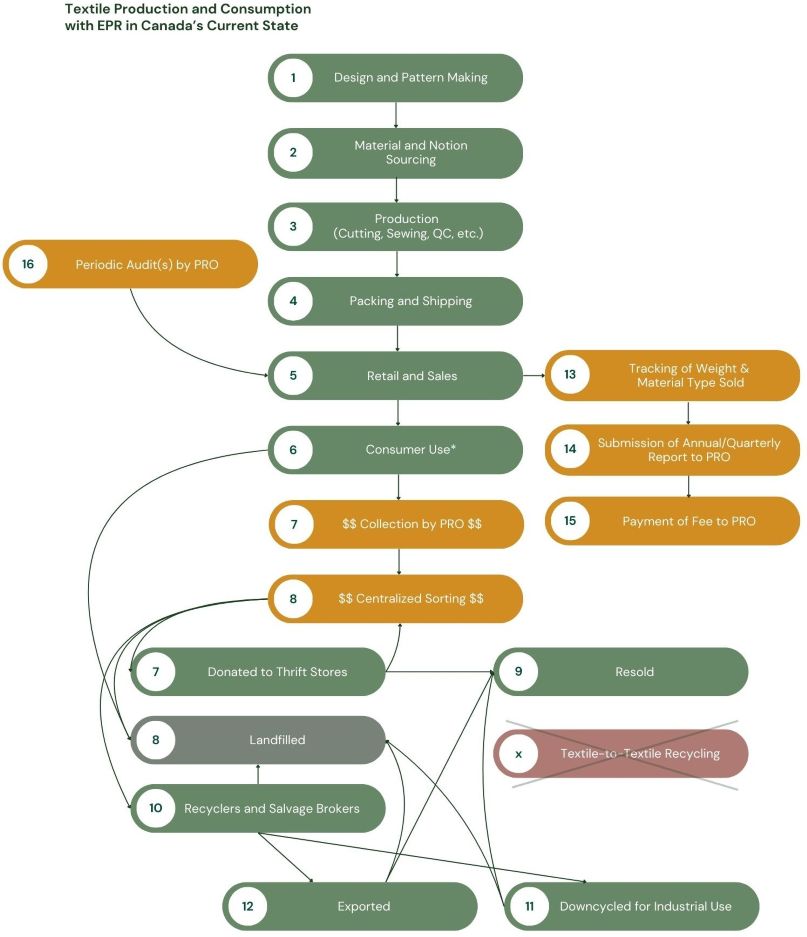

In Canada’s current landscape, the introduction of EPR wouldn’t change where used textiles ultimately end up—it would only change who manages them. The key difference is the introduction of a Producer Responsibility Organization (PRO), which would take over the routing of unsellable clothing from thrift stores and oversee the entire textile disposal process. This is illustrated in the following diagram:

Under EPR, a Producer Responsibility Organization (PRO) would assume control over textile management decisions previously made by thrift stores. Instead of thrift stores deciding how textiles are handled, PROs would centrally manage the sorting and distribution—redirecting them to thrift stores, recyclers and salvage brokers, or landfills.

a) Centralized Sorting

A key component of this model is centralized sorting, which presents significant hurdles in Canada. Currently, sorting textiles is predominantly a manual, labor-intensive process. PROs would initially have to rely heavily on garment tags to identify textiles’ composition. However, tags are often removed, unreadable, or inaccurate, complicating proper sorting. Advanced sorting technologies—such as Near-Infrared (NIR) scanners, hyperspectral imaging, artificial intelligence (AI)-driven sorting systems, and mass spectrometry—are emerging globally but have yet to reach commercial-scale availability in Canada. Without these tools, accurate sorting remains difficult, reducing recycling effectiveness and increasing the likelihood of textiles being downcycled or landfilled.

b) Gaps in Establishing a Circular Economy

Even if accurate sorting can be addressed, a more critical challenge remains: Canada’s lack of textile-to-textile recycling infrastructure. Currently, the primary recycling method available is mechanical recycling, a process where textiles are shredded into nonwoven industrial materials such as insulation or padding. Unfortunately, mechanical recycling results in fibers that are shorter and weaker, limiting their potential use in creating new garments. Advanced chemical recycling, necessary for true circularity—particularly for mixed-fiber textiles—is still at the pilot stage in Canada, with institutions like George Brown College researching how these technologies might be scaled. However, commercial facilities capable of converting post-consumer textiles into high-quality apparel do not yet exist domestically.

c) Potential Impacts on Charitable Organizations

EPR may introduce systemic changes that extend well beyond producers and recyclers—reshaping how charitable organizations participate in Canada’s economy. Currently, charities such as the Salvation Army, Goodwill, and the Canadian Diabetes Association rely on direct public donations of used clothing, serving both as a source of affordable goods for communities and as a critical revenue stream to support social programs.

Under an EPR model, the PRO would assume primary control over the collection, sorting, and routing of post-consumer textiles. While charities may still receive a share of donated clothing, this additional layer of oversight could impact both the volume and quality of textiles they receive, and reduce their independence in deciding how to process or monetize donations. This shift raises important questions: who will receive the most desirable or resale-worthy textiles? Will consumers continue donating directly to charities, or will the introduction of PRO-run drop-off points shift that behavior—particularly if, as seen in some EU jurisdictions, regulations limit or restrict independent collection by charitable organizations? If charities begin receiving fewer or lower-quality items, their resale operations and funding models may be significantly affected.

Beyond the financial implications, there could also be employment impacts. Many charities depend on teams of staff and volunteers to sort, process, and sell donated clothing. If donation volumes decline or if sorting responsibilities shift to the PRO, some of these roles may be reduced or eliminated—affecting both paid jobs and volunteer-based community programs that often serve as employment training or reintegration pathways.

d) New Responsibilities for Fashion Brands

In addition to these infrastructure gaps, EPR introduces substantial new responsibilities for fashion brand owners. Brands would now be required to:

• Track detailed product data, including weight and fiber composition, for all textiles placed on the market.

• Regularly report to PROs regarding their products’ volume and recycling initiatives.

• Pay EPR fees proportional to the volume of textile products placed on the market, funding collection, sorting, and recycling efforts.

• Potentially ensure a minimum percentage of products are recycled, subject to available infrastructure.

• Manage increased administrative tasks, including data tracking, record-keeping, and periodic compliance reporting.

"Advanced chemical recycling, necessary for true circularity —particularly for mixed-fiber textiles—is still at the pilot stage in Canada..."

4.0 Potential Financial and Operational Impacts of EPR on Canadian Fashion SMEs

4.1 Direct Impacts to SMEs

The introduction of EPR would bring new financial and operational challenges for fashion brands—particularly for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and emerging designers. Understanding these potential barriers is crucial to assessing how EPR could reshape the Canadian fashion industry.

The primary concerns fall into five main categories: financial strain, administrative burden, operational challenges, competitive disadvantages, and regulatory uncertainty.

For many brands, these barriers could translate into additional costs, increased time commitments, and complex compliance requirements. Using data from comparable EPR frameworks, the following estimates provide insight into how these obligations could impact fashion businesses. However, actual costs and administrative demands will vary depending on brand size, product complexity, business practices, and the specifics of Canada’s EPR legislation.

| Barrier* | Initial Estimated Cost (CAD) | Ongoing Estimated Annual Cost (CAD) | Initial Estimated Time (hours) | Ongoing Estimated Annual Time (hours) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Financial Burden | $1,000–$2,500 | $1,375–$3,500 | Included in Administrative Time | Included in Administrative Time |

| Administrative Complexity | Minimal direct cost | Minimal direct cost | 50–100 | 50–90 |

| Operational Constraints | $2,000–$4,000 (materials) | $3,000–$5,000 (materials) | 30–60 | 30–60 |

| Competitive Disadvantage | $2,000–$5,000 (margin loss) | $2,000–$5,000 (margin loss) | 20–40 | 15–30 |

| Regulatory Uncertainty | $500–$2,000 (advisory/legal fees) | Minimal direct cost | 20–30 | 10–15 |

| Total Estimate: | $5,500–$13,500 CAD | $6,375–$13,500 CAD/year | 120–230 hours (3–5 weeks) | 105–195 hours/year (3-4 weeks) |

a) Financial Burden

Small fashion businesses and startups typically operate with limited capital and thin profit margins. Mandatory EPR fees, calculated based on material type, weight, and recyclability, could disproportionately impact their profitability, sustainability, and growth potential. This increased financial pressure could limit small businesses’ capacity to invest in product development, marketing, or scaling operations. Additionally, indirect costs such as compliance software, or sustainability consultants could further increase brands’ expenses.

Estimated Initial Investment:

- EPR Registration and Administrative Setup:

- Includes establishing reporting processes, compliance training, and data management systems.

- Estimated cost: $1,000–$2,500 CAD.

Estimated Recurring Investment:

- Annual EPR Fees:

- Charged based on the quantity of textiles placed on the market annually.

- For an average small brand placing 1,500–3,000 kg of textiles/year into the market, at an estimated EPR rate of $0.25–$0.50/kg, annual fees would range from $375–$1,500 CAD.

- Operational Expenses (Indirect Costs):

- Costs associated with ongoing compliance, including recordkeeping software subscriptions, data tracking systems, and reporting software subscriptions, averaging an additional $1,000–$2,000 CAD annually.

| Cost Category | Initial Estimated Cost (CAD) | Annual Ongoing Estimated Cost (CAD/year) |

|---|---|---|

| Registration & Compliance Setup | $1,000–$2,500 | – |

| EPR Fees | N/A | $375–$1,500 |

| Operational & Compliance Costs | Included in administrative setup | $1,000–$2,000 |

| Total Estimated Cost: | $1,000–$2,500 CAD | $1,375–$3,500 CAD/year |

b) Administrative Complexity

Compliance under EPR involves detailed record-keeping, lifecycle tracking, and periodic reporting. Small brands often lack dedicated administrative support, meaning compliance responsibilities will fall on the founder or a small team. Companies will need to establish reliable tracking systems to monitor materials used, waste generated, and product end-of-life pathways, all of which require time and financial investment. Inadequate record-keeping could also result in penalties, adding further pressure on limited budgets.

Estimated Initial Investment:

- EPR Registration and Compliance Preparation:

- Understanding legislative requirements, initial training, and implementing reporting systems.

- Estimated Time Commitment: 50–100 hours (approximately 1–3 weeks full-time).

Estimated Recurring Investment:

- Data Collection, Tracking, and Verification:

- Gathering detailed product data (weight, fiber composition), ongoing inventory management, and ensuring accuracy.

- Estimated Time Commitment: Approximately 40–70 hours/year (about 3–6 hours/month).

- Record-Keeping & Audit Preparation:

- Maintaining compliance records, preparing documentation, and managing data for potential audits.

- Estimated Time Commitment: 10–20 hours/year.

| Task | Initial Estimated Setup (hours) | Annual Estimated Ongoing Commitment |

|---|---|---|

| Compliance & Registration Setup | 50–100 hours | – |

| Annual Data Collection & Reporting | – | 40–70 hours/year (3–6 hours/month) |

| Record-Keeping & Audit Prep | – | 10–20 hours/year |

| Total Estimated Time: | 50–100 hours | 50–90 hours/year |

c) Operational Constraints

The implementation of EPR can limit small businesses’ operational flexibility, influencing material sourcing, manufacturing processes, and overall product design. Businesses may need to shift to materials that are easier to recycle or that align with EPR cost structures, potentially limiting creative freedom. This shift could require additional research and supplier changes, adding complexity to production timelines. Companies that rely on unique textiles or specialty blends may face increased costs if those materials incur higher EPR fees.

Estimated Initial Investment:

- Material Research and Supplier Transition:

- Identifying alternative compliant materials (sustainable, recyclable textiles) and establishing new supplier relationships.

- Initial material trials, testing, and adjustments to production processes.

- Estimated Cost (material trials/sampling): $2,000–$4,000 CAD

- Estimated Time Commitment: 30–60 hours (approx. 1–2 weeks)

Estimated Recurring Investment:

- Premium Costs for EPR-Compliant Materials:

- Ongoing cost premiums of approximately 10–20% for sustainably produced or easily recyclable textiles, impacting overall material expenses.

- Estimated Additional Material Costs: $3,000–$5,000 CAD/year

- Annual Material Sourcing & Management:

- Regularly verifying compliance, ongoing supplier negotiations, and periodic reassessment of materials to remain EPR-compliant.

- Estimated Time Commitment: 30–60 hours/year (2–5 hours/month)

| Operational Activity | Initial Estimated Setup | Annual Estimated Ongoing Commitment |

|---|---|---|

| Material Research & Supplier Transition | $2,000–$4,000 CAD (material trials) | – |

| Compliant Material Premium | – | $3,000–$5,000 CAD/year (10–20% increase) |

| Material Sourcing & Compliance Management | 30–60 hours (initial research & testing) | 30–60 hours/year (2–5 hours/month) |

| Total Operational Impact | $2,000–$4,000 CAD 30-60 hours | $3,000–$5,000 CAD/year 30-60 hours/year |

d) Competitive Disadvantage

Larger, established brands can more readily absorb EPR-related costs due to economies of scale, potentially placing smaller businesses at a disadvantage in pricing and market positioning. Larger companies may also have internal compliance teams to manage reporting requirements, while smaller brands may need to outsource these services or handle them in-house, reducing the time available for creative development and strategic growth. This imbalance may make it harder for new or small brands to remain competitive.

Estimated Initial Investment:

- Market Analysis and Pricing Strategy Adjustments:

- Analyzing competitors’ pricing structures, conducting market assessments, and adjusting pricing strategies to accommodate initial EPR-related costs without alienating existing customers.

- Estimated Margin Loss (due to initial pricing or margin adjustments): Approximately $2,000–$5,000 CAD

- Estimated Time Commitment: 20–40 hours (market research, financial analysis, price adjustments)

Estimated Recurring Investment:

- Reduced Profit Margins due to EPR fees:

- EPR fees and increased operational costs could reduce annual profit margins if brands choose to absorb these costs rather than passing them on to consumers.

- This may amount to approximately $2,000–$5,000 CAD per year in lost margins for an average small brand.

| Competitive Activity | Initial Estimated Setup | Annual Estimated Ongoing Commitment |

|---|---|---|

| Margin Loss (due to price adjustments or initial market repositioning) | $2,000–$5,000 CAD (initial margin adjustments) | — |

| Margin Impact from EPR Costs | — | $2,000–$5,000 CAD/year (margin erosion or reduced competitiveness) |

| Strategic Pricing & Market Analysis | 20–40 hours | 15–30 hours/year (monthly reviews) |

| Total Competitive Impact | $2,000–$5,000 CAD 20-40 hours | $2,000–$5,000 CAD/year 15-30 hours/year |

e) Regulatory Uncertainty

New regulations often bring initial uncertainty, requiring additional time and resources from small businesses to navigate and comply effectively. Because EPR systems can be complex, small brands may need to seek expert advice or legal consultations to fully understand their obligations. Furthermore, if regulatory requirements shift or new categories are introduced, businesses may need to adapt their compliance strategies, creating ongoing administrative and financial burdens.

Estimated Initial Investment:

- Legal and Advisory Consultations:

- Engaging legal advisors or industry experts to interpret initial legislation, clarify compliance obligations, and establish compliant internal processes.

- Estimated Cost: Approximately $500–$2,000 CAD in initial advisory/legal fees.

- Estimated Time Commitment: 20–30 hours (including consultations, training, and developing internal compliance processes).

Estimated Recurring Investment:

- Minimal Direct Costs:

- After initial setup, direct advisory or legal costs are usually minimal unless major regulatory changes occur.

- Monitoring and Adapting to Regulatory Changes:

- Regularly reviewing updates to legislation, monitoring new reporting requirements, and making minor procedural adjustments.

- Estimated Time Commitment: 10–15 hours/year (approximately 1 hour per month on average).

| Regulatory Activity | Initial Estimated Setup | Annual Estimated Ongoing Commitment |

|---|---|---|

| Advisory/Legal Consultation Fees | $500–$2,000 CAD | Minimal (unless significant changes occur) |

| Time for Compliance Adaptation | 20–30 hours (consultation, training, setup) | 10–15 hours/year (monitoring, minor adjustments) |

| Total Regulatory Impact | $500–$2,000 CAD 20-30 hours | Minimal direct cost 10-15 hours/year |

4.2 Other Potential Unquantifiable Impacts

Beyond its immediate financial and administrative demands, EPR may introduce deeper shifts across the fashion industry—changes that are more difficult to quantify but potentially far-reaching. These impacts have the potential to reshape creative expression, limit entrepreneurial growth, and shift market dynamics over time. In particular, concerns have been raised about the policy’s potential to create barriers for aspiring designers, limit product diversity, and heighten risk aversion among small and independent brands.

a) Barrier to Market Entry

High upfront costs, administrative complexity, and regulatory hurdles introduced by EPR could make it more difficult for emerging designers and entrepreneurs to launch their own brands. For many, the additional financial and compliance burdens could be a major deterrent, limiting fresh talent from entering the Canadian fashion industry. Over time, this could stifle innovation and reduce the diversity of perspectives shaping the market.

b) Reduced Product Diversity

The financial and administrative burdens of EPR compliance may push small fashion brands toward standardization, limiting textile variety and discouraging more experimental or niche collections. For many independent designers, the ability to explore unique fabrics, unconventional silhouettes, or artisanal techniques is a defining aspect of their brand identity. However, if EPR fees favor easily recyclable materials or penalize complex textile blends, brands may feel pressured to simplify their offerings to avoid increased costs.

Additionally, the cost of tracking, reporting, and verifying product materials could deter businesses from working with diverse suppliers or offering limited-run collections that require multiple compliance processes. Over time, this could reduce the availability of specialized textiles, diminish creative expression, and result in a more homogenized fashion market where brands prioritize compliance over innovation.

"This highlights a broader issue: sustainability, as defined by major industry players, is often shaped by the Global North and fails to reflect the realities faced by smaller brands. When sustainability policies don’t account for these disparities, they can reinforce exclusivity rather than drive meaningful inclusivity, diversity, and equity in fashion."

c) Risk Aversion

The financial, administrative, and regulatory pressures introduced by EPR schemes may discourage designers and small brands from experimenting with unconventional materials, niche textiles, or avant-garde concepts. Faced with increased compliance costs and complex reporting requirements, these businesses might gravitate toward safer, lower-cost materials that align more readily with EPR mandates, potentially stifling innovation in fabric development and design.

Case Examples: How Regulations Shape Innovation and Risk-Taking

The European Union’s Green Deal and Its Impact on SMEs

The European Union’s Green Deal, aiming for net-zero emissions by 2050, has introduced comprehensive environmental and social reporting requirements for businesses. While promoting sustainability, these regulations have imposed significant administrative burdens and compliance costs, particularly on SMEs. For instance, Italian lingerie maker Yamamay has had to meticulously account for every environmental and social impact of their products, illustrating the extensive bureaucratic challenges faced by businesses under these new mandates. This heightened regulatory environment has raised concerns about stifling innovation and competitiveness within the EU’s textile industry. (Hancock, 2024)

Similarly, Italy’s ‘Made in Italy’ label faces significant challenges due to increasing EU regulations, and supply chain scrutiny. Italian suppliers, already grappling with high energy and labor costs, must invest in software, machinery, and training to comply with new regulations without immediate financial incentives from brands. Smaller suppliers are especially vulnerable, facing high compliance costs and frequent audits. Despite efforts to improve transparency and traceability, inconsistent data collection remains an issue. (Webb, 2024)

Copenhagen Fashion Week’s Sustainability Requirements

Copenhagen Fashion Week (CPHFW) has positioned itself as a sustainability leader, requiring all participating brands to meet strict environmental and ethical criteria. Since 2023, designers must comply with standards on carbon footprint reduction, circular design, and responsible material sourcing to qualify for the official schedule. (Copenhagen Fashion Week, 2025)

While these initiatives aim to push the industry toward sustainability, they disproportionately burden small and emerging brands, which often lack the resources to meet complex compliance demands. This creates barriers to entry, limiting participation in high-profile events and reducing diversity in the industry. (Polimoda, 2025)

This highlights a broader issue: sustainability, as defined by major industry players, is often shaped by the Global North and fails to reflect the realities faced by smaller, minority-owned brands. When sustainability policies don’t account for these disparities, they can reinforce exclusivity rather than drive meaningful inclusivity, diversity, and equity in fashion. (Gaffey, 2024)

5.0 Conclusion

As Canada moves closer to implementing EPR in the fashion sector, the implications for small and medium-sized businesses cannot be overstated. While the policy is positioned as a step toward environmental accountability, its uniform application across all producers—regardless of their sustainability practices—risks creating unintended consequences.

Larger companies, including fast fashion giants, are often better equipped to absorb EPR-related costs, thanks to economies of scale, dedicated compliance teams, and global supply chains. In contrast, small and independent Canadian brands—many of which are already operating with limited resources and a strong commitment to ethical production—may struggle to keep pace. The result could be a system that inadvertently rewards scale over sustainability, creating market distortions that threaten innovation, diversity, and long-term competitiveness within Canada’s fashion ecosystem. And while EPR is intended to apply broadly, it is domestic brands—those most visible and easiest to regulate—that will likely bear the brunt of compliance. This is despite the fact that over 94% of clothing sold in Canada is imported, and that textiles make up just 1.3% to 2.6% of our total landfill waste.

At its core, EPR does not confront the root of the problem: the unchecked overproduction of clothing. It does not ask who is producing too much, how, or under what conditions. Instead, it assumes that assigning financial responsibility—regardless of a brand’s scale or sustainability commitments—will curb waste. And with no operational textile-to-textile recycling infrastructure in place, the end-of-life pathway for most garments will remain unchanged—sorted, downcycled, or landfilled. Without systems to distinguish between regenerative and extractive production models, and without mechanisms to reduce the sheer volume of clothing entering the market in the first place, the policy risks being performative. EPR may redistribute responsibility, but it does little to prevent the harm. If the solution doesn’t support those already leading the shift toward sustainability, then who is it really designed to serve?

The next article in this series will explore how Canadian fashion brands are responding to EPR and what perspectives they bring to the table in shaping the future of sustainable fashion in Canada.

Deborah King

Deborah is a sustainable fashion expert located in Toronto, Canada. She’s an Industrial Engineer with a post-grad in Sustainable Fashion Production. She grew up on the tiny island of Tortola in the British Virgin Islands, and has been sewing her own clothing since the age of 10. She founded Global Measure to help authentically sustainable and ethical fashion businesses stand out from the greenwashing noise through third-party certification.

Curious to explore EPR further or interested in potential collaborations? Dive into our comprehensive Case Study for a deeper understanding.

References:

Copenhagen Fashion Week. (February, 2025). Sustainability Requirements. Retrieved February 3, 2025, from https://copenhagenfashionweek.com/sustainability-requirements

Environment and Climate Change Canada. (November, 2024). Solid waste diversion and disposal. Retrieved February 3, 2025, from https://www.canada.ca/en/environment-climate-change/services/environmental-indicators/solid-waste-diversion-disposal.html

Fashion Takes Action. (June, 2021). FTA A Feasibility Study of Textile Recycling in Canada. Retrieved November, 1, 2024 from https://www.fashiontakesaction.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/FTA-A-Feasibility-Study-of-Textile-Recycling-in-Canada-EN-June-17-2021.pdf

Gaffey, C. (September, 2024). Scandinavian showcase sets a new bar for the fashion industry. The Times. Retrieved February 3, 2025, from https://www.thetimes.com/world/ireland-world/article/scandinavian-showcase-sets-a-new-bar-for-the-fashion-industry-msww30x5w?region=global

Hancock, A. (September, 2024). Is red tape strangling Europe’s growth? Financial Times. Retrieved February 3, 2025, from https://www.ft.com/content/4e8e6cde-d0ce-4f0a-a7ea-1c913d4dad50

Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada. (August, 2021). Apparel Industry Profile. Government of Canada. Retrieved February 3, 2025, from https://ised-isde.canada.ca/site/consumer-products/en/industry-profiles/apparel

National Association for Charitable Textile Recycling (April, 2019). A Tipping Point:

The Canadian Textile Diversion Industry. Retrieved February 3, 2025, from https://nactr.ca/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/The-Canadian-Textile-Diversion-Industry-April-2019.pdf

Observatory of Economic Complexity. (n.d.). Used clothing trade between Canada and the world. Retrieved February 3, 2025, from https://oec.world/en/profile/bilateral-product/used-clothing/reporter/can

Polimoda. (February, 2025). Conscious Catwalks. Retrieved February 3, 2025, from https://www.polimoda.com/fashion-weeks-sustainability-copenhagen-influence/

Statistics Canada. (April, 2024). Waste materials diverted, by type and by source (Table 38-10-0138-01). Retrieved February 3, 2025, from https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=3810013801

United States Environmental Protection Agency. (November, 2024). Textiles: Material-Specific Data. Retrieved February 3, 2025, from https://www.epa.gov/facts-and-figures-about-materials-waste-and-recycling/textiles-material-specific-data

U.S. Government Accountability Office. (December, 2024). Textile Waste – Federal Entities Should Collaborate on Reduction and Recycling Efforts (GAO-25-107165). Retrieved February 3, 2025, from https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-25-107165.pdf

University of Waterloo (January, 2023). New research could divert a billion pounds of clothes and other fabric items from landfills. Retrieved February 3, 2025, from https://uwaterloo.ca/news/new-research-could-divert-billion-pounds-clothes-and-other

Webb, B. (October, 2024). Regulations are weighing down Made in Italy. Vogue Business. Retrieved February 3, 2025, from https://www.voguebusiness.com/story/sustainability/regulations-are-weighing-down-made-in-italy