Key Requirements for EPR Success in the Canadian Fashion Industry

-

Deborah King

- EPR, Fashion, Sustainability

Abstract

The fashion industry ranks among the most polluting industries worldwide, fueled by the excessive production of fast fashion. The rise of fast and ultra-fast fashion has flooded the market with low-quality, disposable garments, resulting in severe environmental degradation, significant public health concerns, and economic burdens on governments struggling to manage the overwhelming textile waste.

To address this, many countries, including Canada, are considering implementing Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) programs. EPR holds fashion producers accountable for the entire lifecycle of their products, including disposal and recycling. Legislation will need to be modified and/or created for provincial waste management mandates to define and include textiles. Successful EPR implementation will require collaboration among federal, provincial, and municipal governments, fashion brands, and industry experts. A comprehensive framework must also define producer obligations and establish Producer Responsibility Organizations (PROs) to manage collection, sorting, and recycling processes.

Developing the necessary infrastructure involves strategically placing textile collection points, enhancing transportation logistics, and creating sorting and recycling facilities. Both mechanical and chemical recycling methods have distinct advantages and limitations, with significant investment required to establish a national recycling infrastructure. Robust data management systems will be essential for tracking textiles through the value chain, ensuring transparency and regulatory compliance.

Implementing EPR will incur significant short- and long-term costs. These financial requirements must be balanced with the economic impacts on small fashion businesses, which comprise 98% of Canada’s fashion landscape. Small businesses will face challenges such as regulatory compliance costs, operational adjustments, and competitive disadvantages. Additionally, the imposition of new taxes and levies to fund EPR could make cheaper, imported garments more appealing, further straining local businesses.

Moreover, EPR may not fully address the root causes of overproduction and the influx of low-quality garments. While it offers a mechanism for consolidating waste, it does not curb the excessive production of disposable fast fashion items. The Canadian fashion industry, government, and local taxpayers will bear the brunt of the costs, while foreign competitors remain unaffected, posing a serious threat to the competitiveness of Canadian brands. EPR would force many fashion businesses to close or consolidate operations with larger brands.

More holistic approaches can be taken to create a truly sustainable and resilient fashion industry in Canada. This includes addressing overproduction, promoting higher-quality garments, and encouraging innovation in recycling technologies.

Want to read this article offline? Download a free copy of this paper here.

Introduction: Current state of the fashion industry

The fashion industry is recognized as one of the most polluting industries globally, with the “fast fashion machine” producing more clothing than the average person can wear in a lifetime. In 2016, Zara curated 24 collections per year, while H&M released 12 to 16 collections annually, refreshing its offerings weekly (McKinsey & Company, 2016). Ultra-fast fashion drop-shipper Shein produces over one million items annually, adding around 2,000 SKUs daily (Lipman, 2024) (Curry, 2024).

All of this excessive production comes at a significant environmental and social cost. To produce cheaper clothing, inferior materials are often used, which do not hold up well in the wash leading to increased textile waste (David Suzuki Foundation, n.d.) (Bick, Halsey & Ekenga, 2018). Additionally, people in underdeveloped countries are frequently employed in these supply chains and are often not paid a living wage (Arce, 2022). In some cases, they work under conditions of forced labor (Whiteman, 2024).

The environmental cost of fast fashion has drawn scrutiny over the past decade for several reasons including:

- Environmental Impact

- The vast scale of fast fashion production has significantly increased global manufacturing, shipping, and associated emissions. This surge in textile production generates considerable waste, contributing to severe environmental degradation (Pacheco, 2024).

- Public health concerns

- Fast fashion disposal disproportionately affects under-resourced communities in the Global South (Wohlgemuth, 2022). Often, discarded textiles are exported to regions lacking the necessary infrastructure to properly process the waste, leading to public health issues (Wohlgemuth, 2022).

- Economic burden

- The fast fashion industry imposes a substantial economic burden due to the increased costs associated with managing textile waste in landfills. The rapid turnover of cheaply made clothing results in significant amounts of waste, necessitating more extensive waste management and landfill maintenance efforts, thereby straining municipal budgets and resources (Igini, 2023).

In response, many countries, including Canada, are considering the implementation of Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) programs to manage textile waste. This concept would hold local fashion producers accountable for the entire lifecycle of their products, including disposal and recycling. Learn more about EPR and how it works here – https://globalmeasure.org/epr-2/

With this increased attention, questions arise about how this framework will practically impact the Canadian fashion landscape. Given the growing focus on EPR as a solution to textile waste, this paper examines what’s needed to make EPR work effectively in the Canadian fashion industry.

We’ll be exploring the following topics:

• The Current Fashion Landscape

• Regulatory Framework for Implementing EPR

• Infrastructure Development Necessary to Support EPR

• Financial Considerations

• Potential Impacts to Small Business

A future paper will examine the practicalities of the nuanced impacts on the industry and the public.

Section 1: Understanding the Current Landscape

In 2018, Canada contributed an estimated 10 million tonnes of waste to landfills (Statistics Canada, 2022). Approximately 60,000 tonnes were diverted through reuse or recycling (Statistics Canada, 2022). It is unclear what percentage of this waste is specifically textiles, as Canada currently lacks the technology to track or sort it. However, the Boston Consulting Group estimates that globally, 83.5 million tonnes of apparel waste are created every year, with textile waste projected to increase by 62% by 2030 (Storry & McKenzie, 2018). Consequently, discussions about EPR have become more attractive to governments. EPR would shift the operational and financial responsibility of waste management back to local manufacturers, alleviating the burden on municipalities.

In Canada, there are approximately 200 mandatory and voluntary EPR programs focused on 30 categories including the following (BanQu, 2023):

• Packaging and paper products

• Electronic and electrical equipment

• Batteries

• Tires

• Automotive materials (e.g., used oil, filters, and containers)

• Pharmaceuticals and sharps

• Household hazardous waste

• Fluorescent lamps and other mercury-containing products

Globally, there are very few active EPR programs addressing textile waste.

Active Programs:

• France: Implemented in 2008 and is considered the most mature textile EPR system. Read more here – https://globalmeasure.org/epr-3-textiles-france/

• Netherlands: Implemented in 2023 with producer obligations to begin in 2025. Read more here – https://globalmeasure.org/epr-3-textiles-netherlands/

• Hungary: Similar to the Netherlands, was implemented in 2023 with producer obligations to start in 2025.

Emerging/Planned Programs:

• European Union: As part of the EU strategy for Sustainable and Circular Textiles, all member states are required to have textile EPR systems in place by 2025.

Other Countries Considering or Developing Textile EPR (Nishimura, 2024):

• Australia

• California, USA

• Norway

• Chile

• Canada – Environment and Climate Change Canada has begun consultations with NGOs and various stakeholders as part of a “proposed roadmap for addressing plastic waste and pollution from the textile and apparel sector” (Environment and Climate Change Canada, 2024)

Section 2: Regulatory Framework

To successfully move forward with a Canadian EPR system for textiles, several types of legislation and regulations would need to be modified or created.

1. Provincial Waste Management Legislation:

In Canada, waste management is primarily managed at the provincial level (Environment and Climate Change Canada, 2024). This means each province would need to amend its existing waste management acts or create new legislation to include textiles as a specific category. To initiate this type of change, stakeholders must first convene and agree on a definition of textile waste. They would need to determine whether textile waste includes clothing, household textiles such as linens, mattress materials, automotive seats, boat sails, and other related items. Provincial targets would also need to be set for collection, reuse, and recycling efforts, aligning with available infrastructure and waste management capabilities.

To ensure the EPR system is cohesive and efficient, provinces must harmonize their collective regulations. This could involve coordination through interprovincial agreements, which would help align reporting requirements and enable a balanced approach to EPR at the federal level, allowing for comparable metrics.

2. Circular Economy Integration:

Nearly every major municipality across Canada has implemented pathways to achieve net-zero carbon emissions (Herbert, Dale & Stashok, 2022). True circularity requires that materials are continually recycled and waste is reduced toward zero waste. To support these broader environmental goals, collaboration is needed at the federal, provincial, and municipal levels. This would ensure that sustainable development policies are prioritized in policy creation, supporting climate change mitigation on a wider scale (EPR Canada, 2017).

3. Federal Support:

Although Canadian EPR regulations are typically set at the provincial level, the federal government could support national implementation. Environment and Climate Change Canada could use its authority to mandate EPR for products containing toxic substances or plastics such as polyester, which they appear to be actively exploring (Environment and Climate Change Canada, 2024). Additionally, federal guidelines could be established to encourage harmonization across the provinces.

4. Producer Obligations:

An integral component of moving forward with legislation governing an EPR system for textiles is clearly defining who qualifies as a “Producer”. France, where an EPR system for textiles is currently operational, defines a producer as “any natural or legal person who develops, manufactures, handles, processes, sells, or imports waste-generating products or the elements and materials used to manufacture them” (Circular Pro, 2024). This means the following groups are subject to EPR legislation in France (Bluesign, 2024):

• Manufacturers/Brand Owners who design and produce new textile products for sale in France.

• Importers who purchase textile products and subsequently resell them in France.

• Businesses selling textile products under their brand or name in France.

• Online retailers based outside France but marketing their products to French consumers.

Click this link to learn more about France’s EPR system for textiles – https://globalmeasure.org/epr-3-textiles-france/

Similarly, Canada would need to determine which entities should be considered producers and outline their specific responsibilities. This includes defining registration requirements, reporting obligations, and associated fees for collection, sorting, and recycling.

5. Producer Responsibility Organization (PRO) Regulations:

In detailing how EPR works in various industries and countries, we described how Producer Responsibility Organizations (PROs) are typically tasked with managing the collection and sorting of materials. Learn more about France’s EPR system for textiles. Legislation would be needed to both establish and govern the operations of PROs for textiles. To avoid creating an unfair market or monopoly, these rules would need to address the formation, operation, and governance of PROs. Transparent reporting requirements would also need to be established to maintain operational integrity.

6. Collection and Recycling Infrastructure:

To support the overarching EPR system, legislation would need to mandate the establishment of collection and/or recycling systems for textile waste. This could involve amending existing municipal or provincial legislation or introducing new legislation. It would need to include guidelines or rules for take-back programs, textile waste collection points, and integration with municipal collection. Additionally, provisions should be made for reporting requirements to maintain the financial integrity of the system.

7. Other Supporting Policies:

Complementary legislation would also be needed to reinforce the effectiveness of a textile EPR system. This includes legislation supporting landfill bans for textiles, surcharges for improper disposal, compliance requirements, penalties for non-compliance, and monitoring and auditing processes. To further enhance the impact of an EPR system, policies should be implemented to promote research and development into recycling technologies, market development for recycled textile materials, and green procurement policies. Additionally, consumer education could be supported by regulations mandating clear labeling and certification of textile products.

Section 3: Infrastructure Development

For a Canadian EPR system for textiles to be successful, critical infrastructure must be established prior to its implementation.

1. Textile Collection

Collection points would need to be strategically placed across Canada. Locations should be optimized to ensure accessibility and fair distribution across both remote and densely populated regions. Preference could be given to community centers, public spaces, existing waste management routes and infrastructure, multi-residential buildings, and educational institutions. Retail locations could also serve as convenient drop-off points for consumers, an approach leveraged in France. (Learn more about France’s EPR system for textiles – https://globalmeasure.org/epr-3-textiles-france/). The frequency of collection would also need to be considered, especially in less populated areas.

2. Transportation and Logistics

Enhanced transportation and logistics would be required to move collected textiles from various collection points to sorting plants, and then to their next phase, which may include recycling or reselling facilities. Logistics must account for the geographic distribution of population densities and the seasonal fluctuations in textile volumes. Balancing the frequency of pickups with transportation costs is critical for cost efficiency, and minimizing the environmental footprint of the vehicles involved. Textiles would need to be collected frequently enough to preserve their quality for potential reuse or recycling. Additionally, remote locations may pose accessibility challenges for larger vehicles. Effective data management will be important to track textiles as they are distributed to various sorting facilities.

3. Sorting

Sorting facilities would need to be located in areas accessible to logistics and transportation. These facilities should be large enough to handle varying volumes of textiles and scalable to accommodate fluctuations in demand. Some countries with existing EPR systems use sorting facilities abroad, which adds further logistical complexities, carbon emissions, and costs (van Duijin et al., 2022).

If based in Canada, sorting facilities would require manual labor to sort textiles by material type, quality, and color. Although there is ongoing research into automated sorting solutions leveraging microscopy, these technologies are still in development and cannot yet handle the variability of textiles in circulation effectively (EPR Canada, 2017) (Arnold, 2019).

During the sorting process, attention must be paid to the presence of contaminants, including non-recyclable materials and mixed fibers. It is crucial to sort textiles in a manner that preserves their quality for reuse, as this is typically a more cost-effective alternative to recycling. Additionally, the process should consider the economic viability of reselling lower-value and lower-quality textiles, such as fast fashion garments. Market demand must be considered to maximize cost savings and avoid unnecessary emissions associated with shipping/transporting clothing to resale locations.

4. Recycling and Processing Infrastructure:

Textiles moving on the recycling stream, and not reuse, may be processed mechanically or chemically.

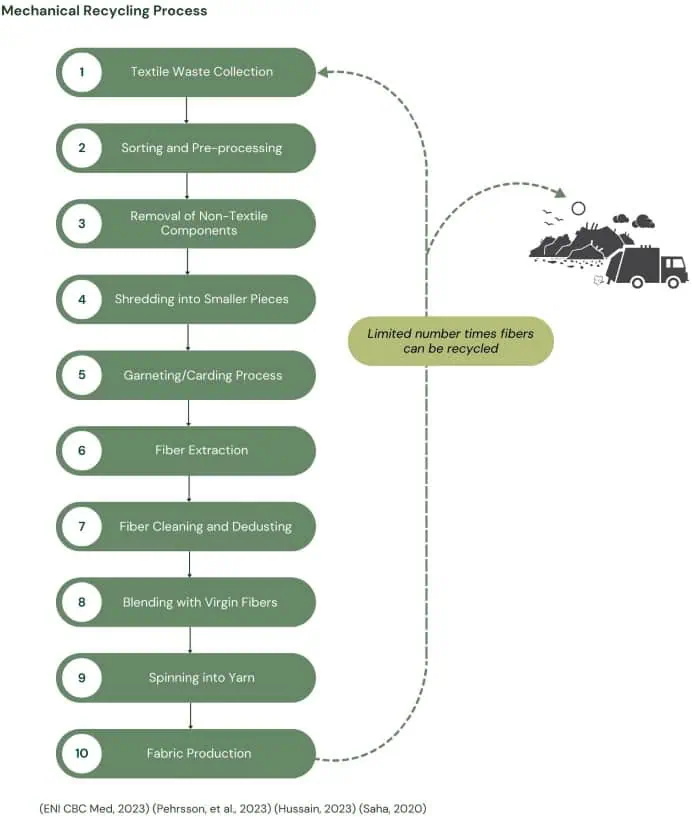

a) Mechanical Recycling

Process Flow:

Process:

• Breaks textiles down by cutting, shredding, or carding.

Types of Textiles:

• The process is most suitable for mono-fiber fabrics such as 100% cotton, but may be used for synthetics like polyester (Saha, 2020) (Kuyichi, n.d.).

Advantages:

• Typically more energy-efficient than chemical recycling resulting in fewer emissions.

• More widely available than chemical recycling.

• Requires less monetary investment compared to chemical recycling.

Limitations:

• Creates shorter fibers that often need to be mixed with virgin fibers for textile use.

• May have limited applications due to material appearance and reduced structural integrity.

Output:

• Materials created are usually a lower quality and often lead to downcycling.

• This process can limit the amount of times materials can be recycled before becoming unusable (Paramount Global, 2024) (Bioplastic News, 2020).

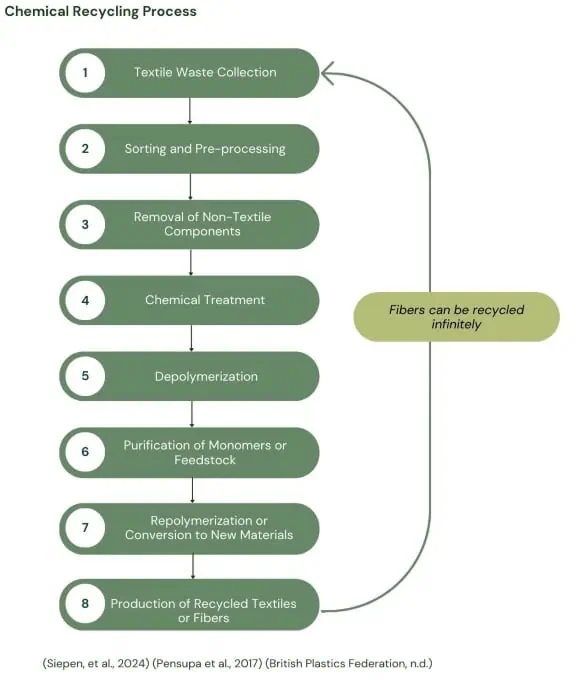

b) Chemical Recycling:

Process Flow:

Process:

• Breaks textiles down into their chemical components (monomers) leveraging various chemical methods including solvolysis, hydrolysis, and gasification (Pensupa et al., 2017).

Types of Textiles:

• Chemical recycling is particularly effective for synthetic fibers like polyester (PET) and polyamide (nylon). It can also be applied to natural fibers like cotton, though the processes differ (Baloyi et al, 2023).

Advantages:

• Produces high-quality recycled materials comparable to virgin fibers.

• Ability to infinitely recycle fibers without quality degradation.

• Enables closed-loop recycling, contributing to a circular economy.

• Potential for infinite recycling cycles without significant quality loss.

Limitations:

• Higher costs and energy are typically required for textile processing.

• Challenges in separating different fiber types in blended textiles.

• Presence of dyes and other chemicals can complicate the recycling process.

• Limited facilities available worldwide with a high initial investment cost estimated around $200 million per plant (Paramount Global, 2024) (Bioplastic News, 2020).

Output:

• Fibers created through this process resemble virgin fibers.

c) Comparison and Additional Details:

While both methods are effective at repurposing spent textiles, there are three key differences between the mechanical and chemical textile recycling processes (Damayanti, et al., 2021) (Pensupa, et al.,2017) (Baloyi, et al., 2023):

i) Process and Output:

• Mechanical recycling involves physically breaking down textiles through cutting, shredding, or melting. The output retains the original chemical structure of the fibers, but in a different physical form (ex. shorter fibers or melted pellets). Fibers must typically be blended with a high concentration of virgin fibers to regain structural integrity for reuse in clothing.

• Chemical recycling breaks down textile polymers into their chemical components through processes like solvolysis. The output raw materials can be repolymerized into new fibers.

ii) Fiber Quality:

• Mechanical recycling often results in shorter, weaker fibers.

• Chemical recycling can produce fibers of comparable quality to virgin materials, as it works with purified chemical components.

iii) Availability of technology

• Mechanical recycling is cheaper and easier to implement.

• Chemical recycling technology is still emerging and not widely available.

Textiles entering recycling streams may need to have components such as buttons, rivets, and zippers removed manually to enable proper recycling (Recycling Inside, 2023). Contaminants like metal zippers and clasps can potentially damage mechanical recycling machinery, and metallic parts pose a fire hazard: a spark caused by a metal fastener striking machine parts could ignite textiles (Xinjinglong, n.d.) (ENI CBC Med, 2023). Separating these components also allows for their reuse, promoting circularity.

It is also important to note that mechanical and chemical recycling infrastructures are not widely available in Canada. Significant investment would be needed to create facilities capable of processing varying textile volumes nationally. France has noted this limitation in their current textile EPR model, and their PRO, Refashion, is seeking to develop recycling infrastructure to further its circular economy goals (Wilson, 2021) (Russell, 2022).

Lastly, mechanically or chemically recycling textile waste can be energy-intensive. It is imperative to balance the environmental benefits of recycling with resource consumption.

5. Data Management Systems:

An integral component for the operation of an efficient and fully circular EPR system is a robust data management system. Producers and Producer Responsibility Organizations (PROs) would need to be integrated into this system to ensure they meet their respective obligations. Digital systems must be established to track the flow of textiles as they are transported through each step of the value chain, enabling transparency, regulatory compliance, and quality control. This system should facilitate coordination among all parties, including producers, collectors, logistics providers, sorters, and recyclers. Additionally, independent auditors would need to be trained on the system to monitor its use and ensure compliance.

6. Market Development Infrastructure:

To effectively implement EPR for textiles in Canada, robust education and outreach initiatives are essential for both consumers and producers.

a) Producers:

Targeted training and workshops should be provided to educate producers about EPR legislation, their responsibilities, and new materials created through recycling efforts. Producers should also be given incentives to adopt circular practices and use recycled materials. Additionally, tools and certifications should be provided to help them market recycled or more sustainable options.

b) Consumers:

Investment is required in consumer education to help them adapt to new processes for disposing of textile waste (ELT Global, n.d.). Campaigns are needed to inform the public about the impacts of textile waste and the importance of recycling. Information should explain how the EPR system works and the types of materials suitable for collection to avoid contamination (Yavari, 2019). Consumers should also be encouraged to make more responsible choices when purchasing clothing, supporting businesses that leverage recycled, sustainable, and/or certified options. Community engagement is crucial to ensure the public knows where to recycle textiles at the end of their life. School programs can also be created to educate younger generations about sustainable textile practices.

Section 4: Financial Considerations

Implementing a national EPR system for textiles in Canada involves numerous financial considerations. Our next paper will explore potential EPR alternatives and their economic impacts. In this paper, we will outline the preparatory, implementation, and ongoing operational costs that various stakeholders will need to account for in an EPR system for textiles (Butler, 2022) (Norton Rose Fulbright, 2023) (Eunomia, 2022).

1. Preparatory Costs:

a) Stakeholder Convening Costs:

i) Meeting and Facilitation Expenses: Labor and administrative costs for organizing meetings, workshops, and consultations among stakeholders to agree on definitions, targets, and regulations. Multiple meetings must be held to ensure adequate representation from various stakeholder groups, including local producers, governmental bodies, and other stakeholders.

ii) Travel and Accommodation: Costs for stakeholders traveling to convene at provincial and national meetings.

iii) Consultation Fees: Costs associated with hiring and/or contracting experts and consultants to facilitate discussions and provide technical expertise.

b) Legislative Amendments:

i) Legal and Administrative Costs: Labor and administrative costs for amending existing waste management acts, or creating new legislation at the provincial level to include textiles.

ii) Regulatory Development: Costs associated with drafting new regulations, conducting impact assessments, and public consultations.

iii) Harmonization Efforts: Expenses for coordinating interprovincial agreements to ensure cohesive and efficient EPR regulations across provinces.

c) Circular Economy Integration:

i) Policy Development: Labor and administrative costs for developing policies to align EPR with broader environmental goals, such as net-zero emissions.

ii) Coordination Costs: Facilitating collaboration among federal, provincial, and municipal levels to integrate sustainable development policies.

d) Federal Support and Guidelines:

i) Federal Mandate Implementation: Costs for Environment and Climate Change Canada to establish (and enforce) EPR mandates for textiles containing toxic substances.

ii) Guideline Development: Creating federal guidelines to encourage harmonization across provinces, including costs for research, stakeholder engagement, and publication.

e) Producer Obligations:

i) Registration and Reporting Systems: Developing systems for producers to register, report obligations, and pay associated fees.

ii) Compliance Monitoring: Determining and establishing mechanisms to monitor and ensure producer compliance, including inspections and audits.

iii) Incentives and Certifications: Providing incentives for producers to adopt circular practices and certifications to market sustainable options.

2. Implementation Costs

a) Producer Responsibility Organization (PRO) Regulations:

i) Formation and Governance Costs: Labor and administrative costs for establishing and governing PROs for textiles, including operational expenses.

ii) Transparent Reporting Systems: Costs for implementing transparent reporting requirements and systems to maintain operational integrity and prevent monopolies.

b) Collection and Recycling Infrastructure:

i) Infrastructure Development: Building and expanding collection systems, sorting facilities, and recycling and processing plants. This also includes purchasing land and developing infrastructure to support recycling and processing facilities.

ii) Data Management Systems: Developing digital systems to track textiles through the value chain, ensuring transparency and regulatory compliance.

c) Supporting Policies and Compliance:

i) Landfill Bans and Surcharges: Labor and administrative costs for implementing legislation supporting landfill bans for textiles and surcharges for improper disposal.

ii) Research and Development: Funding for research into recycling technologies and market development for recycled textile materials.

iii) Consumer Education: Investment in consumer education campaigns to promote responsible disposal and support for recycled, sustainable, or certified textile products.

3. Ongoing Operational Costs

a) Collection and Transportation Costs:

i) Regular Collection Operations: Costs associated with the continuous operation of textile collection points, including staffing, equipment maintenance, and utilities.

ii) Transportation Logistics: Expenses for transporting collected textiles from various collection points to sorting facilities and recycling plants, including fuel, vehicle maintenance, and labor.

iii) Geographic Distribution Management: Additional costs for managing collections in remote and less populated areas, ensuring accessibility and frequency of pickups.

iv) Storage Costs: Expenses related to the storage and handling of textile materials prior to transport to a recycling center, including staff time.

b) Sorting and Processing Costs:

i) Labor Costs: Ongoing salaries and benefits for workers involved in sorting textiles by material type, quality, and color.

ii) Facility Operations: Maintenance and operational costs for sorting facilities, including utilities, equipment upkeep, and safety measures.

iii) Processing Fees: Costs associated with the recycling or processing of textiles, whether through mechanical or chemical methods, including energy consumption and equipment wear and tear.

c) Data Management and Reporting:

i) System Maintenance: Continuous upkeep and upgrading of digital data management systems necessary to track textiles through the value chain.

ii) Compliance Reporting: Regular reporting to regulatory bodies to ensure transparency, regulatory compliance, and quality control, including costs for data collection, analysis, and submission.

iii) Auditing and Monitoring: Expenses related to independent auditors who monitor compliance and verify the accuracy of reporting.

d) Producer Responsibility Organization (PRO) Operations:

i) Administrative Costs: Ongoing operational expenses for PROs, including staffing, office space, utilities, and administrative support.

ii) Governance and Oversight: Costs for governance activities, board meetings, stakeholder engagement, and regulatory compliance.

iii) Transparent Reporting Systems: Maintaining systems to ensure transparent reporting and accountability, preventing monopolistic practices, and ensuring fair market competition.

e) Consumer Education and Outreach:

i) Public Awareness Campaigns: Continuous investment in campaigns to educate consumers about proper textile disposal, recycling options, and the environmental impact of textile waste.

ii) School and Community Programs: Ongoing costs for educational programs in schools and communities to promote sustainable textile practices among younger generations.

iii) Labeling and Certification: Expenses for maintaining and updating labeling and certification programs to help consumers identify sustainable and recycled textile products.

f) Research and Development:

i) Innovation Funding: Regular investment in research and development to improve recycling technologies, develop new materials, and enhance the efficiency of the EPR system.

ii) Market Development: Ongoing efforts to create and expand markets for recycled textile materials, including partnerships with industry stakeholders and marketing initiatives.

g) Monitoring and Compliance Enforcement:

i) Regulatory Oversight: Continuous costs for monitoring compliance with EPR regulations, including inspections, audits, and enforcement actions.

ii) Penalties and Incentives: Administration of penalties for non-compliance and incentives for producers who adopt sustainable practices and meet their EPR obligations.

EPR implementation will incur significant short and long-term costs along with industry disruption. However, developing supporting infrastructure can drive innovation, job creation, and a more circular textile industry in Canada. The financial requirements of these developments must be balanced with the economic impacts on small fashion businesses, which make up 98% of Canada’s fashion landscape (Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada, 2023).

It is important to note that in 2021, the pre-tax profit margin for clothing and clothing accessories stores in Canada was only 7% (Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada, 2023). This figure represents the broader retail sector, including both large and small businesses. Given these low profit margins, fashion businesses may struggle to absorb the additional costs of EPR, potentially facing economic hardships that threaten their viability.

Section 5: Impacts to Small Business:

The financial impacts of implementing a national EPR system for textiles in Canada would result in several short- and long-term economic disruptions for small businesses. While we will explore this further in a future paper, here is a brief list of potential challenges that small businesses will face:

1. Costs to Ensure Compliance

a) Regulatory Compliance: Small businesses will need to invest in systems and processes to comply with new EPR regulations, including registration, reporting, and documentation requirements. This could lead to increased administrative costs, which may be more burdensome for smaller firms with limited resources.

b) Financial Contributions: To develop the EPR infrastructure, producers may be required to contribute financially to cover the costs of collection, sorting, and recycling. For small businesses, these contributions could represent a significant portion of their operating budget.

c) Legal and Accounting Expenses: Fashion brands will incur additional legal and accounting costs to understand regulatory requirements, implement necessary changes, and provide reporting to the appropriate authorities.

2. Operational Adjustments

a) Reworking Supply Chains: Small fashion businesses may need to adjust their supply chains to accommodate new EPR requirements, such as sourcing more sustainable materials or redesigning products for recyclability. This could involve additional costs and time, impacting small businesses’ operational efficiency.

b) Investment in Infrastructure: Companies may need to invest in new infrastructure, such as take-back programs or partnerships with recycling facilities. These investments may be financially challenging for smaller enterprises, as these programs typically only break even at best for fashion brands.

c) Logistics for Remote Locations: Companies operating outside major metropolitan areas like Toronto, Montreal, and Vancouver will face additional challenges in determining logistics for collecting and transferring textile materials. Many customers live in different locations from where they made their purchases, and some may move to another city or province after buying. Most Canadian fashion companies do not have a chain of stores across the country, and many do not have any retail stores at all, making returning items to the original purchase location more complex and expensive. (Investment in centrally located recycling facilities would be more efficient than placing the extra burden of handling returns directly on the producer.)

3. Market Dynamics

a) Competitive Disadvantage: Smaller businesses may struggle to compete with larger firms, which typically have more resources and can adapt more easily to new EPR regulations. This could lead to market consolidation, where smaller players are pushed out of the market or forced to merge with larger companies.

b) Pricing Pressure: The costs associated with compliance and operational adjustments may lead to higher prices for consumers. Small businesses, which often operate on thin margins, may find it challenging to pass these costs onto customers without losing sales.

c) Scalability of Sustainable Fashion: A danger to the sustainability of the Canadian fashion sector is the issue of small companies struggling to achieve scale, particularly if they must merge with larger companies to survive.

4. Cash Flow Challenges

a) Short-term Financial Strain: The initial costs of compliance and adaptation could lead to cash flow issues for small businesses. Many small firms operate with limited cash reserves, making them vulnerable to financial strain during the transition period to an EPR system.

b) Delayed Payments: Economic disruptions can lead to delayed payments from customers or partners, further exacerbating cash flow challenges during the implementation of EPR.

Conclusion

The rise of fast fashion and ultra-fast fashion drop shippers has led to unprecedented levels of global clothing production, resulting in the rapid creation and disposal of inferior-quality garments. This take-make-waste approach has caused environmental degradation, public health concerns, and economic burdens on governments. Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) is a suggested model to help manage the waste generated by shifting the responsibility from municipalities back onto producers (Buckley, 2022).

The development of a national EPR system for textiles in Canada requires substantial economic investment to establish the necessary regulatory framework and infrastructure. This will pose a significant burden on Canada’s small business ecosystem, especially since “small” and “micro” businesses constitute 98% of Canada’s fashion landscape (Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada, 2023). Additionally, it is crucial to consider whether the implementation of EPR will effectively address the underlying issue of the proliferation of lower-quality fast and ultra-fast fashion garments. Until a functional Canadian textile recycling industry emerges, shifting responsibility to fashion businesses to collect materials does not address the need to process these materials within a circular system.

While EPR provides a mechanism for managing the disposal and recycling of clothing produced through global supply chains, it will not cease the influx of lower-quality clothing produced overseas. This approach may inadvertently make “cheaper” clothing options more appealing, as new taxes and levies are placed on Canadian fashion to fund the EPR system, leading to economic hardships for Canadian fashion businesses.

According to the latest Industry Canada report, the pre-tax profit margin for clothing and clothing accessories stores in Canada was just 7% in 2021 (Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada, 2023). Both large and small Canadian fashion companies would be disadvantaged by foreign competitors that do not bear the additional burden of EPR, especially given their lower profit margins. With the significant amount of fashion purchased online from foreign companies like Shein and Cider, this presents a serious threat to competition. The Canadian fashion industry, government, local taxpayers, and fashion producers will need to shoulder the brunt of costs for EPR to function effectively. In contrast, foreign businesses will not be subjected to the same fees and constraints, nor will they face threats to their business models.

Currently, the fashion and apparel industry accounts for 27% of Canada’s e-commerce sector and is expected to grow to almost 34% by 2027 (Bush, 2024). EPR would stifle this growth, forcing many fashion brands to close or consolidate operations with larger brands.

Although EPR offers one potential strategy for managing textile waste, it is imperative to consider the broader implications and challenges. Addressing the root causes of overproduction and the consumption of low-quality garments is essential for creating a truly sustainable and resilient fashion industry in Canada. More comprehensive solutions and thoughtful consideration are needed to tackle the fundamental issues at the core of the problem we aim to solve.

Our next paper will explore whether alternatives to EPR exist and what they might look like.

Want to read this article offline? Download a free copy of this paper here.

Deborah King

Deborah is a sustainable fashion expert located in Toronto, Canada. She’s an Industrial Engineer with a post-grad in Sustainable Fashion Production. She grew up on the tiny island of Tortola in the British Virgin Islands, and has been sewing her own clothing since the age of 10. She founded Global Measure to help authentically sustainable and ethical fashion businesses stand out from the greenwashing noise through third-party certification.

Curious to explore EPR further or interested in potential collaborations? Dive into our comprehensive Case Study for a deeper understanding.

References:

Arce, C. (2022). Crisis response in the global supply chain of the fashion industry [Senior thesis, Claremont McKenna College]. Scholarship @ Claremont. Retrieved July 2, 2024, from https://scholarship.claremont.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3906&context=cmc_theses

Arnold, J. (October, 2019). Extended producer responsibility in Canada. Smart Prosperity Institute. Retrieved July 5, 2024, from https://institute.smartprosperity.ca/sites/default/files/eprprogramsincanadaresearchpaper.pdf

Baloyi, R. B., Gbadeyan, O. J., Sithole, B., & Chunilall, V. (November, 2023). Recent advances in recycling technologies for waste textile fabrics: A review. Textile Research Journal, 94(3-4). Retrieved July 5, 2024, from https://doi.org/10.1177/00405175231210239

BanQu. (September, 2023). The global extended producer responsibility regulations guide. Retrieved July 2, 2024, from https://www.banqu.co/blog/global-extended-producer-responsibility-regulations

Bartik, A. W., Bertrand, M., Cullen, Z., Glaeser, E. L., Luca, M., & Stanton, C. (2020). The impact of COVID-19 on small business outcomes and expectations. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 117(30), 17656-17666. Retrieved July 15, 2024, from https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2006991117

Bick, R., Halsey, E., & Ekenga, C. C. (December, 2018). The global environmental injustice of fast fashion. Environmental Health, 17(1), 92. Retrieved July 2, 2024, from https://doi.org/10.1186/s12940-018-0433-7

Bioplastics News. (November, 2020). What is the difference between mechanical and chemical recycling? Retrieved July 5, 2024, from https://bioplasticsnews.com/2020/11/20/difference-mechanical-chemical-recycling/

Bluesign. (n.d.). Extended Producer Responsibility in France. Retrieved July 2, 2024, from https://www.bluesign.com/en/extended-producer-responsibility-in-france/

British Plastics Federation. (n.d.). Chemical recycling 101. Retrieved July 15, 2024, from https://www.bpf.co.uk/plastipedia/chemical-recycling-101.aspx

Buckley, C. E. (2022). Policies to reduce textile waste in Metro Vancouver [Master’s thesis, Simon Fraser University]. Simon Fraser University Theses Repository. Retrieved July 15, 2024, from https://theses.lib.sfu.ca/file/thesis/6850

Bush, O. (June, 2024). Fashion and apparel industry statistics in Canada. Retrieved July 15, 2024, from https://madeinca.ca/fashion-and-apparel-industry-statistics-canada/

Butler, M. (March, 2022). EPR unpacked: Selected best principles and practices for Extended Producer Responsibility Programs with a focus on Nova Scotia. Ecology Action Centre. Retrieved July 15, 2024, from https://ecologyaction.ca/sites/default/files/2022-06/EPR%20Report%202022%20%281%29.pdf

Circular Pro (n.d.). EPR requirements in France in 2024 – what you need to know. Retrieved July 2, 2024, from https://circular-pro.com/epr-requirements-france-2024-what-need-to-know/

Curry, D. (May, 2024). Shein revenue and usage statistics (2024). Business of Apps. Retrieved July 2, 2024, from https://www.businessofapps.com/data/shein-statistics/

Damayanti, D., Wu, H. S., & Rianjanu, A. (November, 2021). Possibility Routes for Textile Recycling Technology. Polymers. 13. 3834. Retrieved July 5, 2024, from http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/polym13213834

David Suzuki Foundation. (n.d.). The environmental costs of fast fashion. Retrieved July 2, 2024, from https://davidsuzuki.org/living-green/the-environmental-cost-of-fast-fashion/

Divert NS. (2023). Textile Waste: The Impact Of What We Wear. Textile education guide. Retrieved July 15, 2024, from https://divertns.ca/sites/default/files/learning-lesson-plans-downloads/2023-07/Textile%20Education%20Guide.pdf

ENI CBC Med. (2023). A study on technologies for recycling and re-use of textile scraps. Retrieved July 10, 2024, from https://www.enicbcmed.eu/sites/default/files/2023-01/A%20Study%20on%20technologies%20for%20recycling%20and%20re-use%20of%20textile%20scraps%20-%20TMA%20WP6.pdf

Environment and Climate Change Canada. (July, 2024). Roadmap to address plastic waste and pollution in the textile and apparel sector. Government of Canada. Retrieved July 2, 2024, from https://www.canada.ca/en/environment-climate-change/services/managing-reducing-waste/consultations/roadmap-plastic-waste-pollution-textile-apparel-sector.html

ELT Global. (n.d.). Educational outreach. Retrieved July 15, 2024, from https://www.elt-global.com/educational-outreach/

EPR Canada. (2017). Overview of the state of EPR in Canada: What have we learned? Retrieved July 2, 2024, from https://www.eprcanada.ca/reports/2017/Overview-of-the-State-of-EPR-in-Canada-long-version-EN.pdf

Eunomia. (February, 2022). Driving a circular economy for textiles through EPR. Retrieved July 15, 2024, from https://eunomia.eco/reports/driving-a-circular-economy-for-textiles-through-epr/

Herbert, Y., Dale, A., & Stashok, C. (November, 2022). Canadian cities: climate change action and plan. Buildings and Cities, 3(1), 854-873. Retrieved July 2, 2024, from https://doi.org/10.5334/bc.251

Hussain, T. (October, 2023). 3 methods of textile recycling. LinkedIn. Retrieved July 10, 2024, from https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/3-methods-textile-recycling-dr-tanveer-hussain-gzkdf/

Igini, M. (August, 2023). 10 concerning fast fashion waste statistics. Earth.Org. Retrieved July 2, 2024, from https://earth.org/statistics-about-fast-fashion-waste/

Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada. (2023). Businesses – Canadian Industry Statistics: Textile and fabric finishing and fabric coating [NAICS 3133]. Retrieved July 15, 2024, from https://ised-isde.canada.ca/app/ixb/cis/businesses-entreprises/315

Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada. (2023). Retail revenues and expenses – Canadian Industry Statistics. Retrieved July 15, 2024, from https://ised-isde.canada.ca/app/ixb/cis/retail-detail/4481

Kuyichi. (n.d.). Mechanical vs Chemical recycling. Retrieved July 5, 2024, from https://kuyichi.com/blog/mechanical-vs-chemical-recycling

Lipman, N. (April, 2024). ‘Super cute please like’: The unstoppable rise of Shein. The Guardian. Retrieved July 2, 2024, from https://www.theguardian.com/fashion/2024/apr/16/super-cute-please-like-the-unstoppable-rise-of-shein

McKinsey & Company. (October, 2016). Style that’s sustainable: A new fast-fashion formula. McKinsey & Company. Retrieved July 2, 2024, from https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/sustainability/our-insights/style-thats-sustainable-a-new-fast-fashion-formula

Nishimura, K. (January, 2024). Extended producer responsibility schemes could boost textile recycling. Sourcing Journal. Retrieved July 2, 2024, from https://sourcingjournal.com/sustainability/sustainability-compliance/extended-producer-responsibility-epr-textile-recycling-eu-sustainability-legislation-wrap-490188/

Norton Rose Fulbright. (July, 2023). The EU’s proposal for extended producer responsibility for textiles. Retrieved July 15, 2024, from https://www.nortonrosefulbright.com/en-ca/knowledge/publications/d07fc852/the-eus-proposal-for-extended-producer-responsibility-for-textiles

Pacheco, M. (February, 2024). MEPs agree to get tough on fast fashion over environmental impact. Euronews. Retrieved July 2, 2024, from https://www.euronews.com/green/2024/02/15/meps-agree-to-get-tough-on-fast-fashion-over-environmental-impact

Paramount Global. (February, 2024). Mechanical vs chemical post consumer recycled resin. Retrieved July 5, 2024, from https://www.paramountglobal.com/knowledge/mechanical-chemical-post-consumer-recycled-resin/

Pensupa, N., Leu, S. Y., Hu, Y., Du, C., Liu, H., Jing, H., Wang, H., & Lin, C. S. K. (2017). [The drawbacks, advantages and disadvantages of chemically recycling textiles]. ResearchGate. Retrieved July 5, 2024, from https://www.researchgate.net/figure/The-drawbacks-advantages-and-disadvantages-of-chemically-recycling-textiles_tbl2_355982160

Pehrsson, A., Köppe, G., Geldhäuser, S., Krichel, A., Cetin, M., Pohlmeyer, F., Müller, K., & Breton, J. (2023). Redefining textile waste sorting: Impulses and findings for the future of next-gen sorting facilities. Retrieved July 10, 2024, from https://assets.ctfassets.net/io3pirq6e1a9/4pYxCYMNBZu89ahwMRS8tK/788cb588a273bafddf0f031096781b38/White_Paper_TTWif_28-11-23.pdf

Recycling Inside. (March, 2023). Textiles recycling: The sorting challenge. Retrieved July 15, 2024, from https://recyclinginside.com/textile-recycling/textiles-recycling-the-sorting-challenge/

Russell, M. (September, 2022). Increased investment key to accelerating Europe’s textile recycling. Just Style. Retrieved July 15, 2024, from https://www.just-style.com/news/increased-investment-key-to-accelerating-europes-textile-recycling/

Saha, S. (August, 2020). Textile recycling: The mechanical recycling of textile wastes. Online Clothing Study. Retrieved July 5, 2024, from https://www.onlineclothingstudy.com/2020/08/textile-recycling-mechanical-recycling.html

Sanchez, A. (July, 2023). Textile recycling’s hidden costs: Sorting through the mess. LinkedIn. Retrieved July 15, 2024, from https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/textile-recyclings-hidden-costs-sorting-through-mess-sanchez-dmin/

Savage, K. (October, 2023). The impact of inflation on small businesses. U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved July 15, 2024, from https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2023/10/inflation-impact-small-business.html

Siepen, S., Herweg, O., Mair, R., & Popa, D. (May, 2024). How EPCs and equipment suppliers can capitalize on chemical recycling. Roland Berger. Retrieved July 15, 2024, from https://www.rolandberger.com/en/Insights/Publications/How-EPCs-and-equipment-suppliers-can-capitalize-on-chemical-recycling.html

Statistics Canada. (February, 2022). Unravelling the story about household textile and e-waste disposal in Canada. Retrieved July 2, 2024, from https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/11-627-m/11-627-m2022015-eng.htm

Storry, K. & McKenzie, A. (March, 2018). Unravelling the Problem of Apparel Waste in the Greater Vancouver Area. Retrieved July 2, 2024, from http://dx.doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.26792.26886

Textile Exchange. (n.d.). Making textile-to-textile recycling a reality with SuperCircle. Retrieved July 15, 2024, from https://textileexchange.org/textile-to-textile-recycling-supercircle/

van Duijn, H., Papú Carrone, N., Bakowska, O., Huang, Q., Akerboom, M., Rademan, K., & Vellanki, D. (September, 2022). Sorting for circularity Europe: An evaluation and commercial assessment of textile waste across Europe. Fashion for Good. Retrieved July 5, 2024, from https://reports.fashionforgood.com/report/sorting-for-circularity-europe/chapterdetail?chapter=5&reportid=888

Whiteman, A. (January, 2024). Apparel brands still using forced or slave labour in their supply chains. The Loadstar. Retrieved July 2, 2024, from https://theloadstar.com/apparel-brands-still-using-forced-or-slave-labour-in-their-supply-chains/

Wilson, A. (September, 2021). Learnings from France on textile waste and EPR. Innovation in Textiles. Retrieved July 1, 2024, from https://www.innovationintextiles.com/learnings-from-france-on-textile-waste-and-epr/

Wohlgemuth, V. (April, 2022). How fast fashion is using the Global South as a dumping ground for textile waste. Greenpeace International. Retrieved July 2, 2024, from https://www.greenpeace.org/international/story/53333/how-fast-fashion-is-using-global-south-as-dumping-ground-for-textile-waste/

Xinjinglong. (n.d.). Advances in fabric recycling machine durability and longevity. 3 Recycling. Retrieved July 15, 2024, from https://www.3recycling.com/a-news-advances-in-fabric-recycling-machine-durability-and-longevity

Yavari, R. (May, 2019). Analysis of a garment-oriented textile recycling system via simulation approach (Master’s thesis, University of Windsor). Retrieved July 15, 2024, from https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/major-papers/85/